The sparkling cold winter morning lifted the heart but numbed the fingers as Barney sprinted quickly over the squeaking snow from his car to the service shop. There he found Mac, his employer, seated at a service bench bearing some strangely assorted paraphernalia: a red-handled tooth brush, a ten-inch-long glass rod, one square of rough brown woolen cloth and another of pink silk, a couple of coat hanger wire stands shaped like bridge lamps and carrying-pea-sized little white balls suspended by silken threads from the ends of their horizontal arms, and a gaily decorated round tin candy container.

"Okay, I give up," Barney said after a puzzled examination of these objects.

"What the heck are you doing?"

"In the parlance of the day, I'm trying to 'get it all together,' " Mac answered with a teasing grin. "I'm going back to where our line of work really started when Thales of Miletus, about 600 BC, observed that a piece of rubbed amber, called "elektron" in Greek, attracted bits of matter. All the millions of uses for electricity and electronics in our modern civilization can be traced back to that casual observation of electrostatic, or triboelectric, charge. Deciding a review of basic electrostatic principles would not hurt me, I got some books from the library, made those little balls from pith gouged out of the center of branches lopped off trees of paradise, or stink trees, growing in my back yard, made the simple leaf electroscope contained in that candy tin with chewing gum wrapper foil, invoked the spirit of Ben Franklin, and started experimenting, trying to explain everything I saw happen in terms of what I know about electron theory. Never before did I get so much thought-provoking pleasure from such simple home-made apparatus."

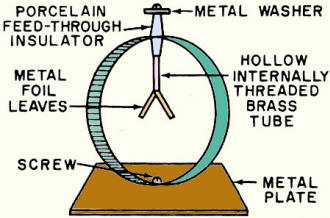

The leaf electroscope is made from a 5" in diameter round candy tin with the bottom cut out. A small porcelain feed-through insulator goes through a hole in one side of the can, and a brass tube with internal threading is screwed onto the bottom end of the insulator. The bottom end of this small-diameter tube is split, and two leaves of foil 1/4" by 2" have their ends clamped in the split. I used thin metal foil from chewing gum and beat it even thinner. Gold leaf, obtainable from a sign painter, would have been better. Plastic wrap is stretched over both ends of the can to allow the leaves to be seen while protecting them from air currents. A brass ball could well replace the metal washer on top of the insulator. When a charge is placed on the washer, either by contact with a charged object or by induction, like charges on the leaves cause them to spread apart. They then collapse when the charge is subsequently taken away.

Electrostatic Induction with Leaf Electroscope

"Aw, I did all that stuff in high school physics," Barney scoffed. "Electrostatic experiments are interesting but of little practical value except to explain how lightning rods work."

"How easy it is to be so cocksure - and so wrong - when you are young!" Mac marveled. "Did you learn that, on a clear bright winter day such as this, the downward electrostatic charge in the atmosphere may carry up to 500 volts per vertical meter?"

"Don't believe it," Barney answered promptly. "That would mean there would be almost 1,000 volts from my head to feet. That would electrocute me."

"Not so. You constitute a grounded conductor, and your skin is an equipotential surface that warps the electric field and makes you unaware of it, even when a thundercloud moves overhead and reverses the field polarity and increases the potential up to 10,000 volts/meter."

"That's when the lightning strikes," Barney interrupted.

"It's not that simple. You need 300 times that voltage, or 30,000 volts/cm, to break down the resistance of air. Actually a 'leader' stroke develops stepwise inside the cloud and comes to ground; then there is a main upstroke along the ionized path of the leader containing tens of thousands of amperes. By the way, did they tell you about earthquake-lightning in your physics class?"

"Nope. We didn't believe in compounding catastrophes."

"Nature apparently does. Flashes of light in the sky often accompany earthquakes. During the Japanese quake of 1930 some 1,500 such flashes were recorded. That quake area is characterized by quartz-rich lava, and it has been suggested that, with the right kind of crystalline order and the right kind of seismic waves, millions of volts of electrostatic energy might be generated by the earth's movement of the rock formation through the piezoelectric effect - the same effect that produces the weak voltage across the output of a crystal phono cartridge when the stylus vibrates in the record groove. Perhaps if any quartz-bearing areas can be found along the San Andreas fault, stations for continuous monitoring of the atmospheric electric field can be set up and their recordings correlated with ground tremors. If these coincide, this might lead to an earthquake early warning system."

"You still haven't shown me that electrostatic electricity is practical."

Practical Applications. Before answering, Mac rubbed the toothbrush handle with the woolen cloth and then held the handle near one of the pith balls. The ball was attracted to the handle and clung to it for a few seconds and then leaped violently away and swung over to a metal meter panel and clung to it.

"That should suggest one very practical use: a precipitator for removing air-polluting fly ash and other liquid and solid particles from flue gases," he said.

"All we need do is put an electrostatic charge on the particles, such as I put on the pith ball, and subject them to a field so they will move toward and cling to an oppositely charged or neutral surface. In practice, this can be done by running a thin wire, carrying a negative potential of 100,000 volts, down the center of a cylindrical duct 20 cm in diameter. The charge produces an average radial field strength of 10,000 volts/cm, but the field strength is much less near the duct wall and much more near the wire. In fact, in the immediate vicinity of the wire it is far above the 30,000 volts/cm I mentioned as being necessary for breaking down the resistance of air. This results in a corona discharge, or zone of ionization, around the wire. Electrons surging off the wire attach themselves to oxygen molecules of the air, converting them into negative ions that are repelled by the wire so they move outward toward the grounded duct wall in a veritable ionic current.

"If a flue gas loaded with waste particles flows up the duct with a velocity of less than ten feet a second, the ionic current charges the particles and makes them move across the gas stream by the billions to collect on the walls of the duct. If the particles are dry, the duct is rapped so the ash falls downward and is collected in a hopper. Liquid particles simply run down the duct walls. Industrial precipitators operate on a negative corona, while home air cleaners use a positive corona. It's estimated such devices trap more than twenty million tons of fly ash a year. I'd call that a practical use."

"So maybe there is one practical use," Barney admitted.

"There's much more. The principle of corona discharge is also used to separate granular mixtures in which the two kinds of particles differ in conductivity so one might be called a conductor and the other an insulator. Remember conductivity is always a relative term. In one form, the mixture comes down from a hopper and spreads out in a thin layer on top of a grounded rotating drum. The drum passes under a wire generating a corona discharge. Ions flood through the mixture to the drum. They pass through the conducting particles to the drum and there is no adhesion; so these particles simply fall off into bin #1 as the drum turns. The charges of ions that strike the insulating particles coat the particle surfaces with a charge that pins them to the metal drum while it moves past bin #1, and they are scraped off in bin #2. This kind of separator is used extensively to separate iron ore, but it is also used to remove rodent excreta from rice, extract garlic seeds from wheat, and to separate nut meats from shells.

"In the handling of continuously moving sheets of paper or film, one surface of which is coated with a sticky substance, the 'web' can be pinned to the surface of a single roller to supply tension by charging the outer surface with ions supplied by a corona discharge.

"Still another important use of the corona discharge is electrocoating, a process used to apply various coatings such as wet paint, grit particles, dry powders, and even short fibers. A spray gun equipped with a corona point emits a fine mist of paint particles that gather the field lines to themselves and attract ions from the corona, thus acquiring a charge. The charged particles are so strongly attracted to the grounded target that they actually curl around it and coat the sides and back surface. It's estimated the saving in paint alone from electrocoating amounts to $50 million a year.

"Flocking is a variation of electrocoating. If you want a velvet wall, you first paint it with conductive aluminum paint to which an adhesive is applied. Then you fill a hopper with short fibers and shake it in front of the wall. As the fibers fall out they are charged from a set of corona points mounted on the hopper, and three things happen: (1) the fibers are driven toward the wall by the Coulomb force of repulsion of like charges, ( 2) the mutual repulsion of like charges on the fibers keeps them apart, and (3) the fibers align themselves with the lines of force so they arrive end-on at the adhesive, permitting more than 200,000 fibers per square inch to be applied. This process is used to make artificial suede, cover the interior of instrument cases, or put pile on carpeting. A similar process is used in the $200 million a year business of coated abrasives, such as sandpaper and emery paper."

"Okay! I'm convinced. Electrostatic electricity is more than a toy," Barney conceded.

"There's more," Mac said relentlessly. "Let's talk about the dry-copy imaging process known as xerography. The operation of a Xerox machine depends on the fact that a selenium-covered plate can be charged by a corona discharge, and then the charge can be removed by exposure to light. In actual operation a selenium-coated drum is charged in the dark from a corona, and then an image of the page to be copied is focused on the drum. The charge is removed in the light areas but retained in the dark areas. Next a 'toner,' a mixture of black dust and tiny glass spheres, is spread over the image. The opposite-charged glass and dust stick together until the mixture reaches the image; then the glass is repelled and the dust clings to the dark areas.

"Now paper that has been charged is spread over the image on the drum and attracts the toner to itself. Finally, this paper moves through a rapid-heating stage that fuses the toner to itself and makes a permanent copy. This is a simplified explanation, of course, but I'm sure that you will get the idea."

"By the way, where did you learn all this stuff anyway?"

"From various books and magazine articles. One of the best sources was the work of A.D. Moore, professor emeritus of electrical engineering at the University of Michigan. Two of his books are Electrostatics and Invention, Discovery and Creativity. He was working on another that may be published by this time called Electrostatics and its Applications. In an article in the March, 1972, issue of Scientific American he points out that Ben Franklin invented the first electric motor, an electrostatic motor; and he goes on to say interest in this type of motor has been revived recently, chiefly by Oleg Jefimenko of West Virginia University. One of his corona motors about five inches long developed a tenth of a horsepower. Recently he put up a wire by balloon and ran one of his motors by energy from the atmosphere's electric field."

"That does it!" Barney exclaimed. "I'm going home tonight and dig out my physics books. How about borrowing those playthings - excuse me, that apparatus - of yours?

"Con mucho gusto," Mac replied, grinning. "That was the whole idea. You'll have fun, and, as a bonus, I'll guarantee it will be much easier to understand solid-state electronics after you've reviewed your electrostatic electricity."